“The way I would think about risk aversion is most people would not want to toss a coin for their entire net worth.”

-Seth Klarman

As we approach the end of an event-filled year for financial markets, the economy, and our nation’s leadership, we felt it would be useful to speak to the notion of risk in the context of the portfolios entrusted to us. What types of risks are we exposed to? And how do we measure and manage risk in order to achieve the best possible outcome?

In “Strategic Risk Taking,” Aswath Damodaran suggests that risk is simply uncertainty combined with a specific, measurable outcome. In the US and other developed economies, we worry about traffic, what to make for dinner, whether we’ll have anyone to talk to at a cocktail party, getting to the gym. We often say “these are first world problems,” because we have a high level of certainty as to the outcome. In our system, even “big” uncertainties, like choosing a life partner, deciding to have children, or a stock market crash, happen in an environment that is generally stable.

However, in a place like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (where the Evangelical Covenant Church is very active), daily life is rife with uncertainties and instability. Even the most solid and thoughtful of risk management plans are often overshadowed by the insurmountable realities of living in a third world country.

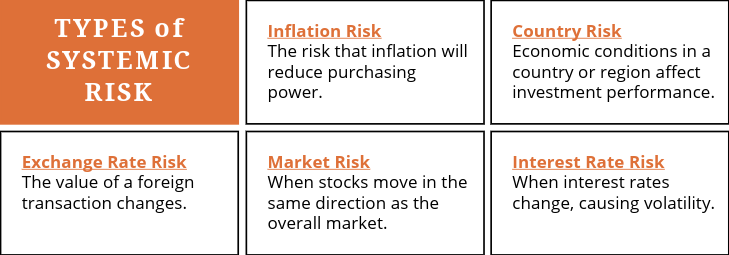

This contrast highlights the first important distinction when talking about risk: systematic risk vs. idiosyncratic risk. In a developed economy, systematic risks are relatively low, whereas in a third world country, systematic risk is high, even to the point where idiosyncratic risks—those linked to individual decisions or circumstances—are often outweighed by the impact of systematic risk.

Shifting gears into the investment world, the majority of risk in your investment portfolio is linked to some type of systematic risk, i.e., simply being exposed to the US stock market, or to global bonds, as an example. The diagram below highlights the main types of systematic risk:

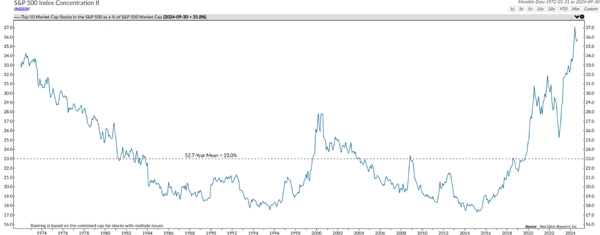

Market risk is high today, particularly in the US stock market, due to the concentration of just a few names in the US equity index. While the S&P 500 has exceeded expectations in 2024, on the back of 2023s already stellar performance, the majority of this performance is linked to a handful of names: Nvidia, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Tesla and Netflix, affectionately-dubbed the “Magnificent Seven.” Investors have jumped on this bandwagon with the expectation that the US equity market can continue to rise ever higher. This is a type of systematic risk called concentration risk or, put simply, “putting all your eggs in one basket.”

To put this in historical perspective, consider that today, the top ten stocks in the S&P 500 (as defined by their market capitalization), represent over 35% of the index. This is higher than at any point in the last 50 years:

You might be asking, why is the market more concentrated than it has ever been? This opens the door to another important component of risk: risk factors.

A risk factor is simply a characteristic that explains performance, either positive or negative. For the above tech companies, their stock prices may be affected by the same things, from the price of the materials used to build microchips, data centers and electrical grids used to supply power, to companies’ or consumers’ appetites and ability to pay for their services. As long as demand for their services and products are strong, and as long as they are able to charge prices that exceed their costs, we can reasonably expect them to perform well. The above two conditions depend on both systematic and company-specific factors.

Shane Parrish writes that in the face of uncertainty, positioning is paramount: “There are two ways to handle such a world: try to predict or try to prepare.” Since we are not in the business of predicting markets, the best way to prepare is to diversify across the risk factors that we expect to be rewarded.

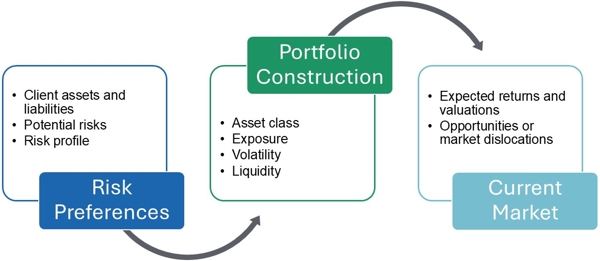

While we alluded above to the risk factors driving technology companies’ performance, other risk factors contribute to the performance of bank, utility, or consumer goods stocks, and much more. Ideally, a long-term investment portfolio should be able to capture performance from a broad variety of risk factors. This is the foundation of diversification as a core risk management tool: by allocating to a range of investments that are impacted at different times by different risk factors.

Keeping the above in mind, at Covenant Trust, we build portfolios first and foremost in line with the “risk factors” that are specific to your family or organization: time (your investment horizon), risk tolerance, and liquidity and spending needs. Your resulting risk profile is aligned with a portfolio that is expected to deliver the growth, risk management, and purchasing power to meet your objectives.